Aileron

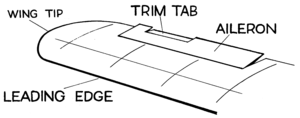

Ailerons are hinged flight control surfaces attached to the trailing edge of the wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. The ailerons are used to control the aircraft in roll, which results in a change in heading due to the tilting of the lift vector. The two ailerons are typically interconnected so that one goes down when the other goes up: the down-going aileron increases the lift on its wing while the up-going aileron reduces the lift on its wing, producing a rolling moment about the aircraft's longitudinal axis. [1] Ailerons are usually situated near the wing tip, but may sometimes be situated nearer the wing root. The terms "outboard aileron" and "inboard aileron" are used to describe these positions respectively. The word aileron is French for "little wing".

An unwanted side effect of aileron operation is adverse yaw—a yawing moment in the opposite direction to the roll. Using the ailerons to roll an aircraft to the right produces a yawing motion to the left. As the aircraft rolls, adverse yaw is caused primarily by the change in drag on the left and right wing. The rising wing generates increased lift, which causes increased drag. The descending wing generates reduced lift, which causes reduced induced drag. The difference in drag on each wing produces the adverse yaw. There is also often an additional adverse yaw contribution from a difference in profile drag between the up-aileron and down-aileron.

Adverse yaw is effectively compensated by the use of the rudder, which results in a sideforce on the vertical tail that opposes the adverse yaw by creating a favorable yawing moment. Another method of compensation is differential ailerons, which have been rigged such that the downgoing aileron deflects less than the upgoing one. In this case the opposing yaw moment is generated by a difference in profile drag between the left and right wingtips. Frise ailerons accentuate this profile drag imbalance by protruding beneath the wing of an upward-deflected aileron, most often by being hinged slightly behind the leading edge and near the bottom of the surface, with the lower section of the leading edge protruding slightly below the wing's undersurface when the aileron is deflected upwards, substantially increasing profile drag on that side. Ailerons may also be designed to use a combination of these methods.[1]

With ailerons in the neutral position, the wing on the outside of the turn develops more lift than the opposite wing due to the variation in airspeed across the wing span, which tends to cause the aircraft to continue to roll. Once the desired angle of bank (degree of rotation on the longitudinal axis) is obtained, the pilot uses opposite aileron to prevent the angle of bank from increasing due to this variation in lift across the wing span. This minor opposite use of the control must be maintained throughout the turn. The pilot also uses a slight amount of rudder in the same direction as the turn to counteract adverse yaw and to produce a "coordinated" turn wherein the fuselage is parallel to the flight path. A simple gauge on the instrument panel called the slip indicator, also known as "the ball", indicates when this coordination is achieved.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kermode, A.C. (1972), Mechanics of Flight, Chapter 9 (8th edition), Pitman Publishing Limited, London. ISBN 0-273-31623-0